10 Things From WWE's Past Newer Fans Won't Believe

Dogs beating wrestlers?!

Aug 29, 2018

If you've read enough of my works by now, you may have noticed the perpetual gleam of nostalgia in my theoretical eye, as I extol the virtues of the good old days of wrestling throughout many of my lists and diatribes. Pseudo-historians like myself take something of a hipster track when it comes to the wrestling of old, turning up our noses at change. Why change? Doesn't everybody know that wrestling perfected itself in 1991?

Kidding/not-kidding aside, I do find some amusement in the responses to the old school-sentimental pieces that I write because they usually fall into one of two groups: either head-nodding agreement (spurring the same eye-gleams) or mild incredulousness. Sometimes I forget just how much time has passed between the time I started watching (in 1989) and today. Literally, there are staffers both on screen and off at Cultaholic who were born *after* I watched WWE programming for the first time. That's a bit sobering.

For this list, I'll be playing the "Back in *my* day" card, and playing it with authority. I'm gonna rattle off some things about the wrestling in my youth, particularly WW(F)E, that would sound a little silly to fans who grew up watching a more recent product. Lemme just take a swig of my Geritol here first...

And not even in the contrast-intended Tommaso Ciampa way, either. There was just simply a point in time where some wrestlers had entrance themes, while others did not. A quick sweep of the 40 wrestlers who competed at Survivor Series 1989 shows that 28 wrestlers (mostly babyfaces) had music, while 12 did not.

Among those who didn't have songs at that point in time: Ted DiBiase, Andre the Giant, Hacksaw Jim Duggan, Greg Valentine, Bad News Brown, Ronnie Garvin, and others. Going back earlier, wrestlers like The Hart Foundation didn't have music, especially as heels prior to the spring of 1988. It wasn't until about 1993-94 that it was decided: "You know, maybe *everybody* that isn't a jobber should have their own music." And even then, Bob Backlund (the Ciampa of his day?) remained an exception.

As you get ready for what feels like the 57th combination of Bayley and/or Sasha Banks vs. some Riott Squad member or combination on Raw, know that it wasn't always that way. You younger fans likely have some inkling that the older days were prone to include at least a handful of jobber squashes, but really, that's mostly what you got 30 years ago.

Weekend airings of Superstars and Wrestling Challenge were almost uniformly squash matches, exhibition wins for name wrestlers against local fodder, while Prime Time Wrestling on Monday nights would feature lower-level talents squaring off, with maybe a feature match or two featuring midcarders. With the exception of title changes that occurred at TV tapings, the best you could hope for was Tito Santana vs. Butch Reed, or The Killer Bees vs. The Islanders. Unless it was Saturday Night's Main Event, you weren't getting Hogan vs. the cream of the heel crop.

This is something that has to be appreciated about modern productions with one-hour shows, i.e. Lucha Underground. If you watch Lucha regularly, you don't see the top names wrestle each time out, and it does help from burning the audience out on valuable performers. Contrast that to Raw or SmackDown, where Seth Rollins, Finn Balor, The New Day, and others have matches weekly, and it kills their specialness - especially when they face other pushed wrestlers on each show.

Back in the day, maybe Big Boss Man and Brutus Beefcake would have matches this week, and maybe they wouldn't. Maybe they'll be on next week, though. And that was the nature of the programming then - the less-is-more approach employed by WWE kept top stars from being overexposed. If you saw Ultimate Warrior run through a jobber on Saturday's episode of Superstars, you may not see him until Challenge the following week, following by a week where he doesn't wrestle at all. With 40-50 main roster wrestlers in the shuffle, there was more variety and novelty in play.

Remember when IMPACT began taping like 10-15 shows in a matter of a few days, and people made fun of them because it was a sign that the company was circling the drain? It's a savvy money-saving move, even if it seems kinda alien in this era of Raw and SmackDown emanating from a different mid-to-large sports venue each week.

But back in the day, WWE would use a similar strategy. Every three weeks, WWE would tape three episodes of Superstars on either a Monday or Tuesday, before taping three episodes of Challenge the following day. And this wasn't during lean times - this was when Hulkamania and Macho Madness ruled the roost, so the places would be packed with excited fans. And the episodes didn't air immediately, either. Depending on the era, episodes of WWE TV taped in mid-August might not begin airing until mid-September, which was fine in the pre-internet days, as spoilers weren't running rampant. Ahh, simpler times.

These days, you go to a WWE live event, and it's little more than just a chance to see the top stars of the company up close. They're a mostly secondary or tertiary part of the business model today, behind rights fees and Network subs and whatnot. But back in the day, house shows were a *major* source of business, hence the purpose of the weekend programming - to drive fans to those cards.

If you lived in the New York area, you had events at Madison Square Garden and in North Jersey's Meadowlands every month. The Superstars and Challenge shows were tailored to different syndicated markets, so that Hogan, Savage, and the rest would hype their upcoming matches at the Garden "next week" or "tonight" or whatever. If you lived in Philly, Hogan would record a similar promo for his big match at the Spectrum. Same for Los Angeles' Sports Arena, Chicago's Rosemont Horizon, and so forth. Wrestlers would record dozens of promos at a time to promote forthcoming house show matches, each airing in different parts of the country - because money lay in house shows.

Before 1993, when the dust settled post-WrestleMania, you didn't get another WWE pay-per-view until SummerSlam in August. King of the Ring stepped in to bridge that five-month gap, but prior to 1995, there certainly weren't pay-per-views each month. As such, storylines could stretch out a little bit more without there needing to be a match or an action beat every week to keep things going.

Saturday Night's Main Event would play a role, airing five to seven times a year, sometimes as a pay-per-view supplement, other times as a gap-filler. But truly, The Big Four really was The Big Four at one time. WrestleMania and SummerSlams were the shows that had the big blowoffs, while Survivor Series and Royal Rumble were novelties that got everybody involved with the titular gimmick matches. There were no Clash of Champions or Fast Lanes to feign excitement about back then.

It's hard to imagine anything moving Monday Night Raw off of its embedded pivot these days, but there used to be a time when WWE had to defer to other USA Network programming. Thankfully, we're not talking about insipid puke stains like Chrisley Knows Best, but rather a pair of annual occurrences that have at least a wee bit more prestige.

Every February for years, Raw (and even predecessor Prime Time Wrestling) would be pre-empted on USA by the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show. Meanwhile, in the SummerSlam time frame, the shows would get the boot in favour of US Open tennis coverage. In the latter half of the nineties, WWE would counter by airing special Friday or Saturday editions of Raw to bridge the gap. This also may explain why SummerSlam used to be a Monday night endeavour at the end of August, to replace a lost Prime Time or Raw episode. Can you imagine Raw taking a backseat to dogs or tennis today?

Thanks to the internet, fans know who just about everybody in wrestling is these days. Someone like Curtis Axel has been a part of the WWE product for about a decade, and he's gone from being Nexus-era Michael McGillicutty to Heyman Guy Axel to various incarnations of doofus Axel (from "DON'T CHANGE THE CHANNEL" to hapless henchman to B-Teamer). Through each role, he's been functionally the same guy, with little attempts to hide who he was before.

Go back a ways and you'll see this wasn't always the case. Very little connection was ever made between US Express-era Mike Rotunda and Irwin R. Schyster, presented as two entirely different people. When Iron Sheik became Colonel Mustafa in 1991, his previous life as Sheiky Baby was all but expunged, and Mustafa was apparently an entirely new person. Waylon Mercy and Dan Spivey weren't the same people, ditto Ricky Steamboat and the man simply known as "The Dragon" in 1991. These days, a wrestler's past gets worked into their on-screen identity. In the days of kayfabe, a new gimmick washed everything else away.

When surrendering to a submission hold these days, a vigorous tap of the hand is used as a visual cue, letting everyone know that the trapped grappler is calling it quits. That didn't become en vogue in WWE until the ankle-breaking Ken Shamrock joined the fold in 1997, as his UFC heritage actually presented a useful idea into the wrestling business.

Prior to that, you just had to take the referee's word on submissions. The victim would flail their arms, grimace through ostensible pain, and occasionally cry out in agony. You may even hear them screaming, "Yes!" or "I give up!" or something to that effect, but mostly, the surrender wouldn't be picked up by the broadcast mics. You only knew a submission finish had taken place when the referee called for the bell. This is, however, one change that a fossilized fan like myself can get behind. In a business that presents itself with broad and overt strokes, a visual cue like tapping out is helpful and even colourful.

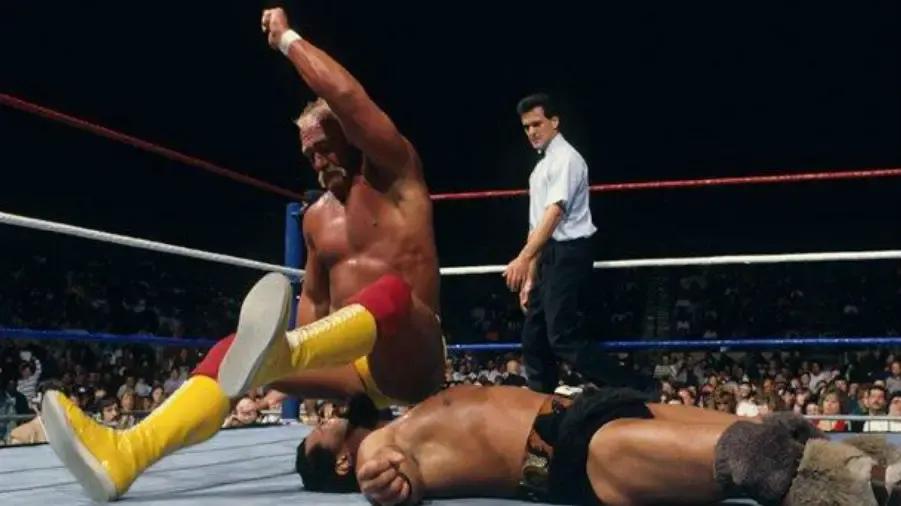

When Hulk Hogan kicked out of Randy Savage's flying elbow smash at WrestleMania V, it was a bit stunning, since nobody, *nobody*, kicked out of someone's Game Over finishing move. Hogan's Leg Drop? Instant death. Savage's elbow, prior to 'Mania 5? Pull the plug. The Road Warriors' Doomsday Device? Call CSI, and tell 'em to bring their kits. Hogan kicking out of Savage's elbow stunned because it was an unlikely occurrence.

These days, it takes three finishers, a ton of harsh landings on the ring apron, and 14 signature moves to slay the #12 contender to the Universal title. When Braun Strowman finished Kevin Owens with a solitary Powerslam at SummerSlam, people were waiting for the kickout because, jeez, only two minutes have elapsed. Instead of believing that a 385-pound man crushing an opponent into a hard canvas, moments after bouncing the back of said opponent's skull off of a metal ramp, would be the end, the instinct was: "Well, he has to kick out, so that they can do more moves." While the previous example was change I could get behind, this is anything but. Let the finishers finish.